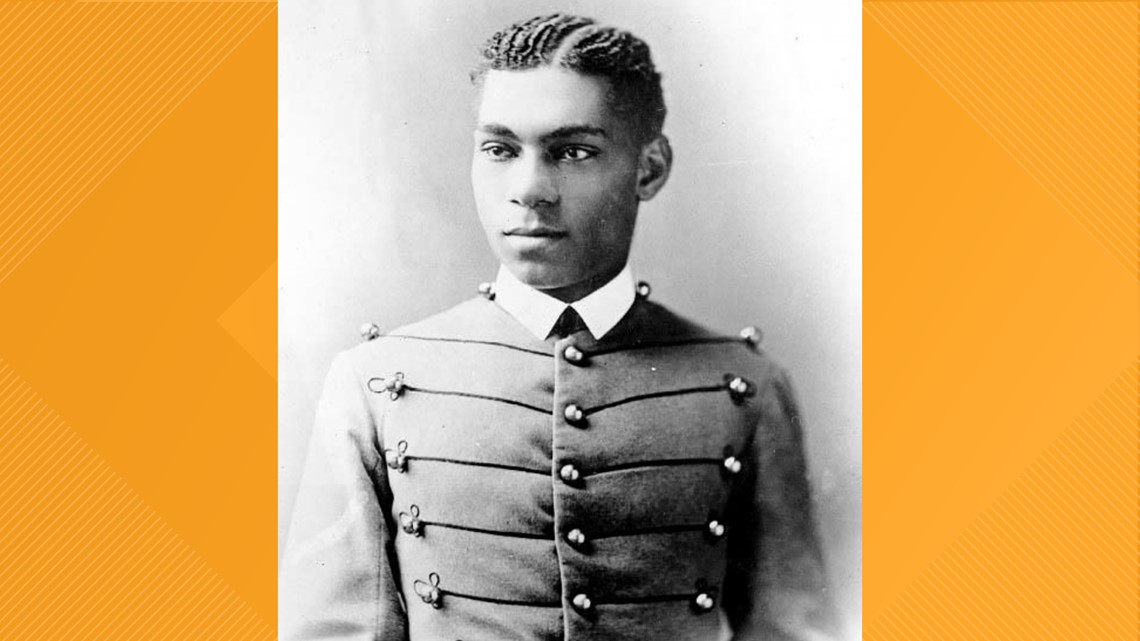

SAN ANGELO, Texas — He was born in 1856. He was West Point’s first Black graduate. He was the first Black commissioned officer in the regular U.S. Army. He was the engineer of a drainage system that is now a National Historic Landmark. He surveyed and supervised construction of a road from Fort Sill, Oklahoma to Gainesville, Texas. He spoke Spanish and French. He was dishonorably discharged by the U.S. Army in 1881. He was issued a posthumous, honorable discharge by the U.S. Army in 1976. He was fully pardoned in 1999, this time by the President of the United States.

143 years is an unusually long story for any one person to have this side of the bible.

Henry Ossian Flipper made an impression wherever he went, and one of those places was San Angelo, Texas. Seriously, how many folks who live here for three months have their name on a street sign?

He may not have realized it when he was doing a soldier’s routine, manual labor at Fort Concho in the summer of 1880, but he was already on a historic journey.

“Flipper got here in June of 1880. He stayed until September,” Fort Concho Historian Evelyn Lemons said. “It was a fairly typical time for the Fort. In the late 70s, early 80s, they were mapping, they were doing patrols. It was more routine duty. There was a lot of telegraph building, that type of thing.”

Everyone who met Flipper at that point in time was experiencing a significant first, whether they knew it or not.

“When he came to Concho, he was an officer with Company A of the 10th Cavalry, which was one of the two Black cavalry units,” Lemons said. “He was the only Black officer here. He was the only Black officer in the Army at that point.”

Although his work at Fort Concho was brief and routine, less than two years earlier, when he was stationed at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Flipper helped stop the spread of malaria by designing a water drainage system.

“It’s called Flipper’s Ditch. Still there, still works,” Lemons said.

After Fort Concho, Flipper was sent to Fort Davis in the rocky hills of southwest Texas. It was there that his military career would come to an end after he was made quartermaster.

“The way the Army worked, a lot of times whatever officer got stuck with that position ended up having to lend his own money, or borrow money. And [Flipper] was charged with embezzlement,” Lemons said. “The bookkeeping was kind of sketchy at times, because you couldn’t always get the funds to pay off the guy that was delivering the hay, so maybe you paid him off and then you took the money back out. Not completely above-board but not completely immoral either. And that was done by all officers that ended up with these tasks. You can look through the records, you can find numerous examples of this.

"But Flipper didn’t get away with it. And actually the charge of embezzlement was dropped, but he was also charged with the overarching, conduct unbecoming an officer. And everybody got charged with conduct unbecoming an officer. You could call somebody a name and get charged with conduct unbecoming an officer. Some of them were really serious, some of them were very frivolous, but that’s the charge that got him kicked out of the Army. Basically, he got railroaded. He did something that any other white officer would have done and gotten a slap on the wrist and been put back to work, and it would just go away.“

The court-martial was swift, and rigged. Fort Davis’ commanding officer, Col. William Rufus Shafter, by all historical accounts, did not like Flipper. The reputation of being the first and only Black officer in the United States Army would no doubt precede him, no matter what fort he was assigned to.

“The whole case was kind of a farce,” Lemons said. “The prosecuting attorney was the one who also ran the court-martial, which is not supposed to happen. And three of the jurors were under Shafter in the chain of command, and that also should never have happened. And Flipper lived to be 84, I believe. So he lives a long life. And he goes on to have a great civilian career. But you know, it plagued him for his whole life.”

Flipper’s family would later pick up the fight he never gave up on to regain his commission.

With an engineering degree, in the late 1800s, Flipper didn’t have much trouble finding work after the Army, Lemons said.

“He got jobs with mining companies, he got jobs surveying. He did a lot trying to reconcile Spanish land grants, to sort out who legally owned what land in Arizona and New Mexico. So he had a very lucrative, positive career after the Army.”

The legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers was, and still very much is, essential to the perseverance of America. Although Flipper’s historically-accomplished military career was unjustly cut short by the time he was only 25 years old, he overcame mind-bogglingly frustrating odds his entire life.

And he was born into slavery in a still relatively young and tumultuous country only a few generations ago.

For context, Mark Matthews, the last surviving Buffalo Soldier (and also a WWII vet) died in 2005, right around the time many Millennials were heading off to college.

A very select few, to the United States Military Academy at West Point.